Bayard Wootten

“A trailblazer for women photographers in the South, North Carolina’s Bayard Wootten (1875-1959) overcame economic hardship, gender discrimination, and the obscurity of a small-town upbringing to become the state’s most significant early female photographer. This advocate of equality for women combined an artistic vision of photography with determination and a love of adventure to forge a distinguished career spanning half a century. Originally trained as an artist, Wootten worked in photography’s pictorial tradition, emphasizing artistic effect in her images at a time when realistic and documentary photography increasingly dominated the medium. ”

South Carolina Low Country (1932-6)

Bayard Wootten

This essay is copyrighted by the Charleston Renaissance Gallery (Charleston, South Carolina) and may not be reproduced or transmitted without written permission from Robert M. Hicklin, Jr. Inc.

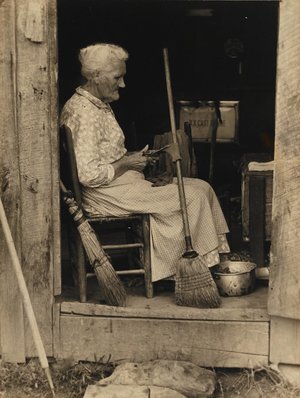

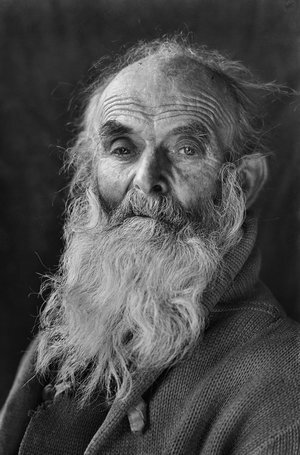

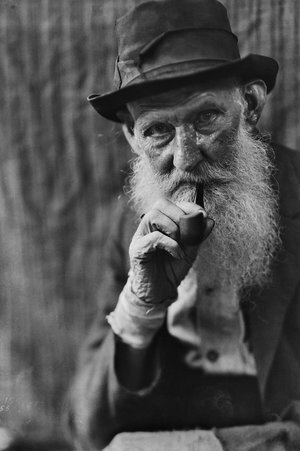

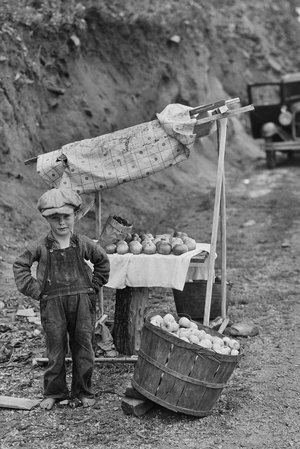

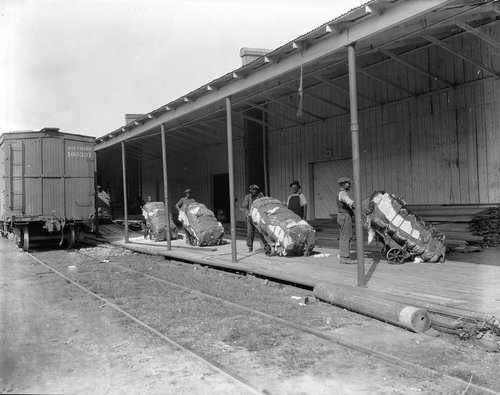

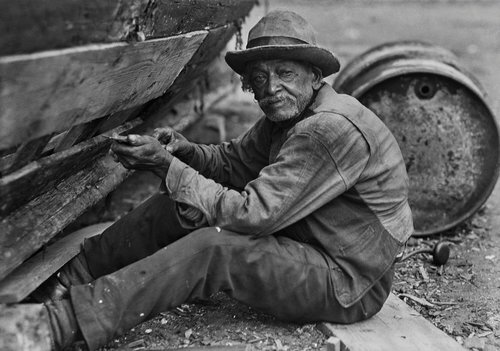

One of the South’s leading photographers of the early twentieth century, Bayard Wootten created ahighly selective body of work ranging from evocative nature studies and botanicals, to haunting images of black and white field workers, to Appalachian mountaineers. Originally trained as apainter, Wootten worked in photography’s pictorial tradition, emphasizing artistry in her images at atime when documentary and straight photography increasingly dominated the medium. Like her contemporary, New York photographer Doris Ulmann, she traveled widely throughout the Carolinas, Tennessee, and Alabama, producing an insightful photographic record of obscure people and places.

At the height of her career in the 1930s, Wootten maintained a sample book she called “Camera Studies.” The collection of original silver gelatin prints, uniformly measuring ten-by-thirteen inches,included selections of the artist’s favorite works. The images of Charleston presented herein arefrom this portfolio.i Taken during visits Wootten made to the area, six of these Lowcountry photographs ultimately appeared in Charleston: Azaleas and Old Bricks, published by Houghton Mifflin in 1937.

Born into a cultured Southern family, Mary Bayard Morgan Wootten grew up in her grandparents’antebellum house in New Bern, North Carolina. Her maternal grandmother and namesake was Mary Bayard Clarke, a highly regarded poet and editor. Wootten’s father, who died when she was only fiveyears old, was a stereoscopic view photographer. She began her own art education under herartistically talented mother’s tutelage. Wootten also studied photographic retouching before attending the North Carolina Normal and Industrial School (now the University of North Carolina-Greensboro) from 1892 to 1894, where she received most of her formal training. That fall, she taught school in Arkansas, and later in Georgia. Following a brief marriage, she returned to New Bern in 1901.

Wootten turned first to painting and then to photography as a means of support for her two children. Having exhausted local study opportunities, she undertook instruction in Asheville with Nace Brock, a talented painter and pictorial photographer who became her mentor. Along withinspiring Wootten’s embrace of the pictorial style, Brock instilled in her an enduring concern for filling a frame in a beautiful way: “The camera is not a free agent as brush or pencil,” she observed, “but relentlessly records things as they are. So the artist must bring to her aid strong contrasts oflight and shade, artistic grouping and rhythmic lines. To use a camera as a means of artistic expression, a certain quality of spirit must be brought to aid light and air.”ii

Like many pictorialists, Wootten balanced commercial portraiture and artistic endeavors, relying on paying clients to finance her creative photography. She was successful from the start. After establishing a studio in New Bern in 1906 and operating branches elsewhere in the state, Wootten moved to the university town of Chapel Hill in 1928. There, she and her half-brother George Moulton opened a multi-service studio. It was during this period that Wootten—now financially stable and free of the responsibilities of child rearing—pursued her artistic interests with single-minded focus.

The University of North Carolina took advantage of Wootten’s presence soon after her arrival in Chapel Hill. Several of her pictures appeared in the University Press’s The Story of North Carolina(1933). Charles Wilson’s Backwoods America (1934), a book about the Ozarks, contained over thirtyWootten photographs, and she contributed more than a hundred images to Muriel Sheppard’s Cabin in the Laurel (1935). This book, which included portraits and landscapes made in the Carolina Blue Ridge, received a host of favorable reviews. Critics found the artistic qualities of Wootten’s landscapes reminiscent of her grandmother’s poetry. As one observed, Wootten’s photographic images reveal “a lightness of touch, vividness, depth of conception, strength of imagery, rhythmic beauty, [and] love of nature.”iii

Landscapes and flowers were a common theme in the watercolors Wootten painted at the turn of the century. In the early 1930s, she turned to similar subjects in photography. Guided by the friendship and botanical insights of horticulturist William Lanier Hunt, she developed a series of lecture programs on important gardens of the South. For this purpose, she toured the southeastern coast from 1933 to 1936, photographing grand homes and formal gardens—sometimes processing black and white film in hotel bathrooms, and exhibiting botanical studies as she traveled. Her itinerary included plantations in Wilmington, Savannah, and Mobile. The historic city of Charleston was a favorite destination, as well as the Lowcountry gardens of Magnolia, Belle Isle, Middleton, and Cypress plantations. She was also drawn to the scenery at Folly Island and composed a number of exquisite landscapes there, including several versions of Folly Island, SC and Folly Island Oaks, S.C.

Wootten began visiting Charleston around 1932, sometimes traveling in the company of Maude Waddell, a poet and feature writer for the Charlotte Observer. Waddell, though born and raised in North Carolina, kept a home in Charleston, and Wootten was a frequent guest. She did not travel lightly. Her large format view-camera required a tripod and a carload of photographic equipment. Like most landscape specialists, Wootten preferred early and late daylight sun, and occasionally camped outside to capture the desired effect. Influenced by the Japanese approach to landscape, she favored diagonal arrangements and spent hours—sometimes days—selecting the best camera angle. Her highly controlled technique impeded spontaneity, but it was effective in the landscape and architectural photography that became her specialty.

During this time, Wootten attempted to penetrate the national publishing market by placing photographs with a New York agency; in the end, however, personal contacts proved more effective. Her photographs of Charleston came to the attention of the Houghton Mifflin Companythrough Fant Hill Thornley, a student at the University of North Carolina who collected Wootten’swork.iv Released in 1937, Charleston: Azaleas and Old Bricks celebrated through photographs and textthe grandeur of the historic city. Wootten’s name appeared on the book’s spine and title page, alongwith that of Charleston historian Samuel Gaillard Stoney, who authored the manuscript. Wootten dedicated the volume to Thornley.

Reproductions in the Charleston book were by photogravure, and the format was larger than that ofany of the artist’s previous publications. She considered it her crowning achievement. “This is my great adventure,” she declared. “In a way it is for me the fruition of my long career as aphotographer.”v

In 1939, Wootten contributed photographs to New Castle, Delaware, 1651-1939 and provided landscape and architectural photographs for Old Homes and Gardens of North Carolina, published by the North Carolina Press and the Garden Club of North Carolina. Her final illustration assignment wasOlive Dargan’s From My Highest Hill: Carolina Mountain Folks, published by J. B. Lippincott in 1941.

In addition to continuing her photographic work, Wootten became a popular lecturer and was well known on the national circuit until an eye hemorrhage ended her career in 1948. At the time of herdeath in 1959, newspapers characterized Wootten as a “distinguished artist” and an “eminent American photographer.” Her accomplishments have been memorialized in the published studies ofher career and by the 1980 establishment of the Bayard Wootten Collection at the University of North Carolina Library.

Nancy Rivard Shaw

i Charlene Harless (Gallery C., Raleigh, North Carolina), telephone conversation with the author, March 2008.

ii Greensboro Daily News, 1926, as quoted in Jerry W. Cotten, Light and Air: The Photography of Bayard Wootten (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 91.

iii Caroline Hickman, “Graphic Images and Agrarian Traditions,” in Graphic Arts & The South: Proceedings of the 1990 North American Print Conference (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993), 255.

iv Cotten, 46.

v Raleigh News & Observer, December 1937, as quoted in Cotton, 46. Additional sources:

Rosenblum, Naomi. Documenting a Myth: The South as Seen by Three Women Photographers – Chansonetta Stanley Emmons, Doris Ulmann, Bayard Wootten, 1910 –1940. Exhibition catalogue. Portland, Oregon: Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Gallery/Reed College, 1998.

Wooten, Bayard and Samuel G. Stoney. Charleston: Azaleas and Old Bricks. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1937.

North Carolina Mountains

South Carolina Low Country ; Downtown Charleston & Surrounding Plantations (1932-6)

Single Mother,Pioneering Photographer: The Remarkable Life Of Bayard Wootten

August 21, 2019 | By Rena Silverman Jan. 29, 2018 for Lenscratch

In 1904, a photographer in North Carolina lent a 4×5 camera to a divorced single mother. He shook his head and muttered several times that she’d “never make the grade.” One year later, he viewed her as his competitor and took back his equipment. So, Bayard (pronounced BY-ard) Wootten, who until then had supported her family by selling small paintings and drawings, went out and bought her own camera.

“She made more than a million images in her life,” said Anthony Lilly, who has written a biopic of Ms. Wootten using her old typewriter. “She illustrated six books with her photography. Most of the government buildings in North and South Carolina used her wall mural photography. It was pictorial photography.”

Though known as a pictorialist (more of an art photographer than a straightforward documentarian), Ms. Wootten strayed from the unspoken rules set by Alfred Stieglitz, the father of pictorialism, in the early 20th century. Unlike Mr. Stieglitz, who was way up north in New York, Ms. Wootten did not oppose commercial photography. In fact, financial gain, believe it or not, was the chief reason she entered the industry, where she nonetheless notched several firsts in her career.

Her first small studio was adjacent to her family home, where she focused on personal postcards, a thriving business at the time. Soon, she had earned enough to move to the business district. And after that, she moved to Camp Glenn, where she sought business from a National Guard summer training camp a few miles away. She sold thousands of postcards in just one summer and eventually asked if she could set up a small studio on the grounds. The general agreed and gave her the title of “Chief of Publicity,” which then made her the first woman in the North Carolina National Guard.

She wore her uniform every day.

PhotoBayard Wootten in her homemade National Guard uniform. Circa 1907-1910.Credit North Carolina Collection, UNC Chapel Hill Libraries

It doesn’t take much to imagine some of the challenges that she, the only woman in sight, faced at Camp Glenn. Military men called her names such as, “Sandfiddler” and “Ole Campaigner,” though she was in her early 30s. So, what motivated her to keep going?

“Financial responsibility to her children and family as well as her drive to be made equal in the male-dominated career,” Mr. Lilly said.

That led Ms. Wootten to reportedly become the first woman to take an aerial photo in America. And, according to her son and Mr. Lilly, she even designed the original Pepsi-Cola logo for her next-door neighbor, who invented the soft drink.

In 1928, Ms. Wootten moved to Chapel Hill, where she portrayed subjects unique to the South, most notably, including the “photographic record of black and white Americans in the lower reaches of society,” according to her biography “Light and Air,” by Jerry W. Cotton.

“In North Carolina you don’t approach somebody’s property,” said Mr. Lilly. “You figure in 1900 until late 1930s she was going into the back roads and approaching people and taking these pictures of former slaves, sharecroppers, tobacco workers.”

She was helped in her work by her ability to put people at ease.

“No one was ever alarmed when she came in,” said Joe Eudy, Ms. Wootten’s close friend who worked at one of her studios in Chapel Hill. “She could go to the mountains of North Carolina and those people are mighty skittish about people they don’t know, but they would invite her to spend the night and have supper. She just had a way of talking to people.”

Ms. Wootten, who died in 1959, was a uniquely southern artist, the kind Sally Mann described in her autobiography, “Hold Still,” as having a “susceptibility to myth and their obsession with place, family, death and the past.” Ghosts haunt the exposure tricks of Ms. Wootten’s earlier plates while the southern sky hangs over several generations of family. Toward the end of her life, as she started to go blind and deaf, she retired to New Bern and lived with Mr. Eudy, whose wife was her niece.

“She was a wonderful person and loved to talk about deep things like philosophy and religion,” said Mr. Eudy. “She also drank wine every night. She drank Redman Wines, which came from the grocery stores. And she smoked cigarettes, one after the other, and played gin rummy by herself.”

Even after she suffered an eye hemorrhage in the late 1940s when she was in her 70s, and she could no longer carry her camera around, she continued to work in her studio, washing and drying prints, making proofs, and talking to customers.

“I have always been chasing something,” she wrote in a letter to a mentor. “But one of the surprises that life has held for me is that I am happier as an old woman than I ever was as a young one. Perhaps the reason for this is that I realized now it does not matter whether we arrive. The joy is in the going.”