Eudora Welty

“A good snapshot stops a moment from running away.”

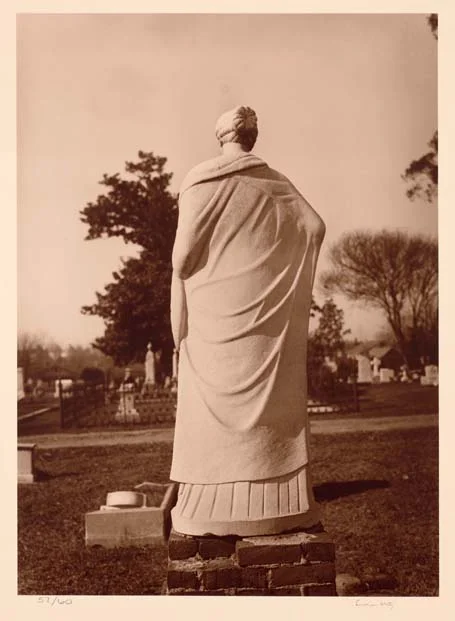

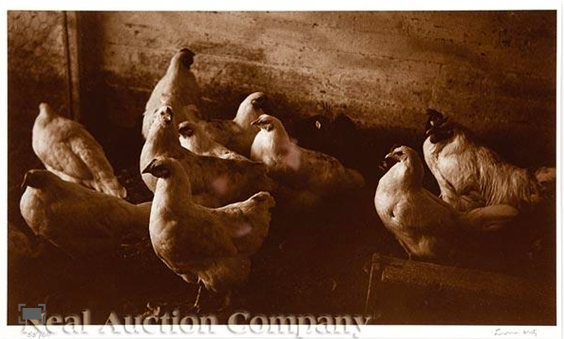

20 Photographs : Portfolio

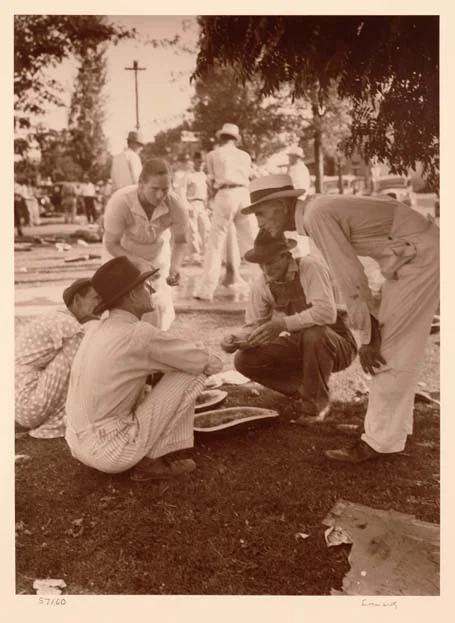

Portfolio includes the following gelatin silver photographs (11 x 14”) mounted, signed and numbered. Printed in 1980. 75 were printed.

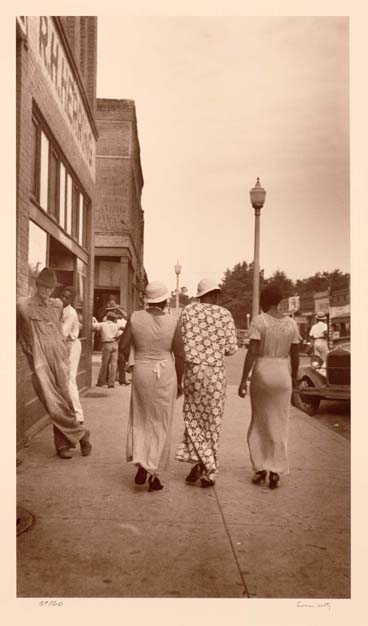

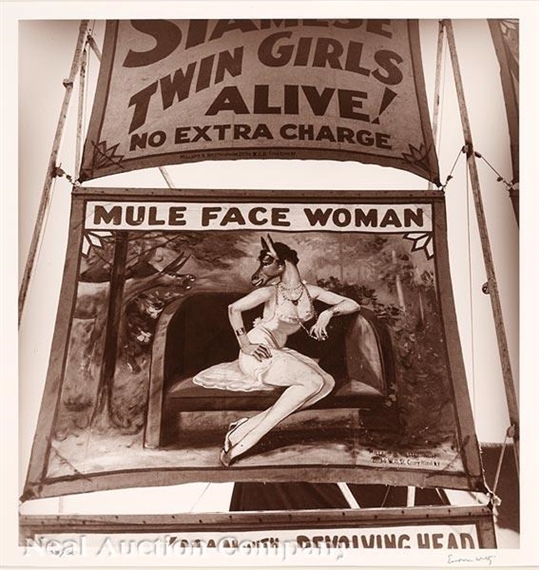

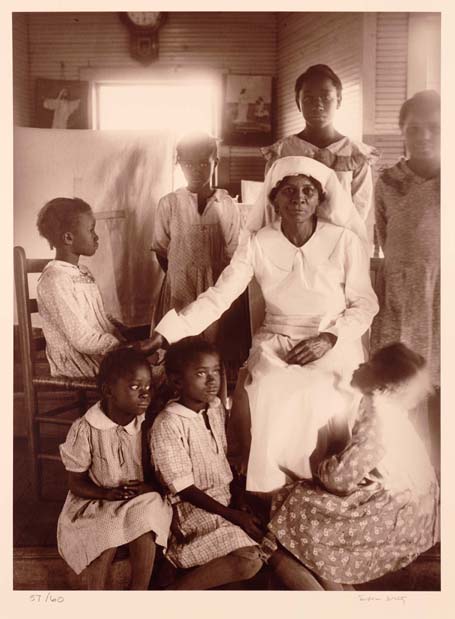

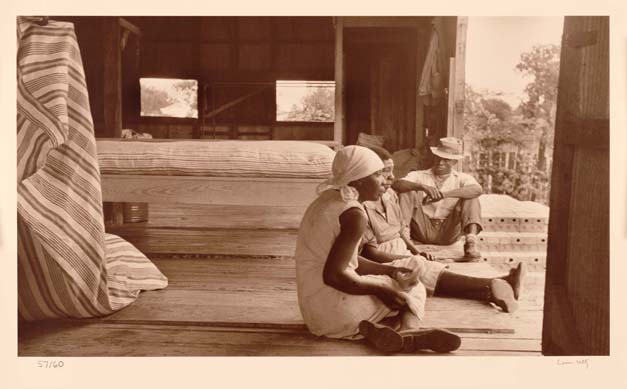

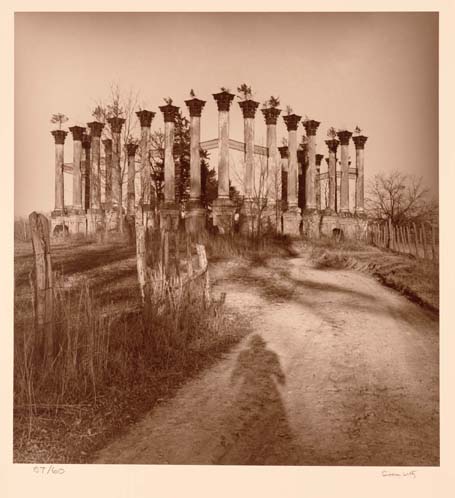

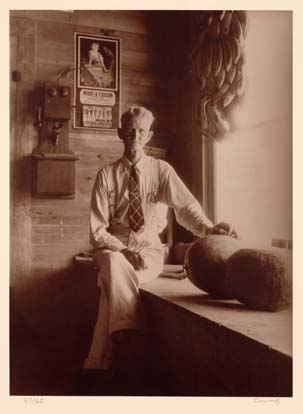

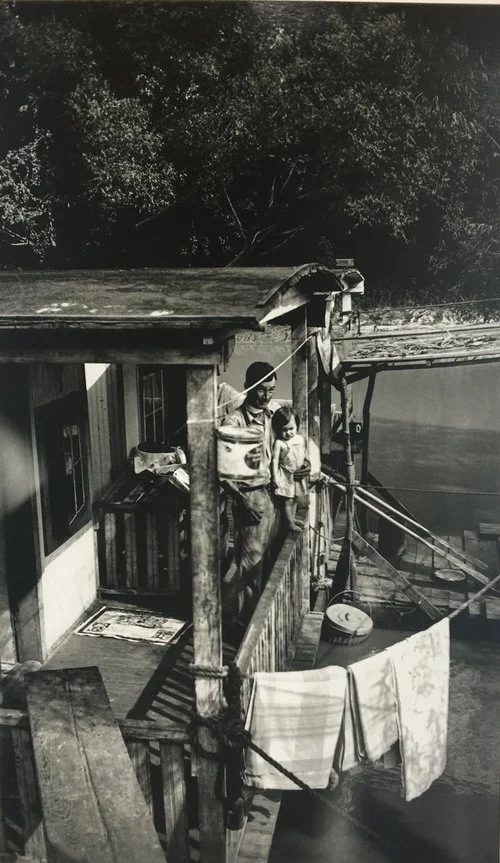

Welty, Eudora. Eudora Welty : Twenty Photographs : 1. A Woman of the 'Thirties, 1935 ; 2. Old Midwife (Ida M'Toy) 1940 ; 3. Mother and Child, 1935 ; 4. Delegate, 1938 ; 5. Child on the Porch, 1939 ; 6. Preacher and Leaders of the Holiness Church, 1939 ; 7. Chopping in the Fields , 1935 ; 8. Tomato Packers' Recess, 1936 ; 9. Saturday Trip to Town, 1939 ; 10. Courthouse Town, 1935 ; 11. Saturday Strollers, 1935 ; 12. Store Front, 1940 ; 13. Side Show, State Fair, 1939 ; 14. Houseboat Family, Pearl River, 1939 ; 15. A House with Bottle Trees, 1941 ; 16. Ruins of Windsor, 1942 ; 17. Ghost River-Town, 1942 ; 18. Abandoned "Lunatic Asylum" 1940 ; 19. Carrying Home the Ice, 1936 ; 20. Home by Dark, 1936 ([United States?] : Palaemon Press Ltd., Winston-Salem, NC, © 1980 ; (Jackson, MS : Gil and Gib Ford) Photographic prints & Brochure in Portfolio. Matted. Boxed Set. 22 items. 26 p. Note : Set 1 of 20 sets with each photograph autographed & numbered by Welty on the matte ; brochure autographed on first page by Welty ; brochure includes A Word on the Photographs & Table of Contents with dates of photographs ; formerly owned by Stuart Wright; Source : Ludlow Addition Box 204/45.

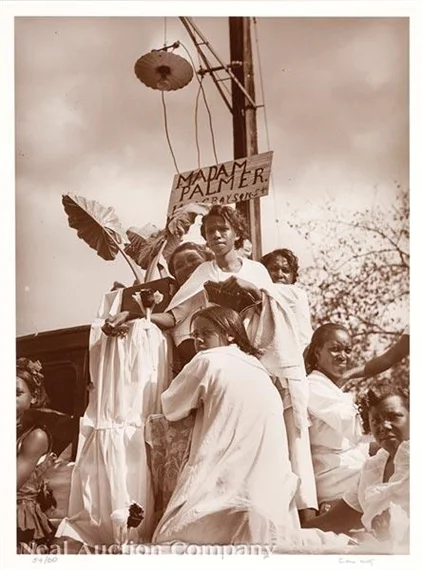

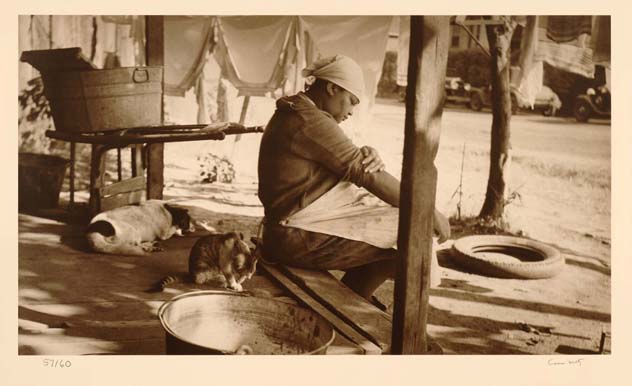

18 Photographs : Portfolio

Portfolio includes the following sepia-toned silver gelatin photographs (1 3/8'' x 12 5/8'') ; signed and numbered. Printed 1992. 60 were printed.

Contemporary Portfolio

Portfolio includes the following silver gelatin photographs 11 x 14 ; numbered with estate stamp. Printed 2017.

Eudora Welty

BY SUZANNE MARRS : Eudora Welty Foundation Scholar-in-Residence, Millsaps College

Born in 1909 in Jackson, Mississippi, the daughter of Christian Webb Welty and Chestina Andrews Welty, Eudora Welty grew up in a close-knit and loving family. From her father she inherited a “love for all instruments that instruct and fascinate,” from her mother a passion for reading and for language. With her brothers, Edward Jefferson Welty and Walter Andrews Welty, she shared bonds of devotion, camaraderie, and humor. Nourished by such a background, Welty became perhaps the most distinguished graduate of the Jackson Public School system. She attended Davis Elementary School when Miss Lorena Duling was principal and graduated from Jackson’s Central High School in 1925. Her collegiate years were spent first at the Mississippi State College for Women in Columbus and then at the University of Wisconsin, where she received her bachelor’s degree. From Wisconsin, Welty went on to graduate study at the Columbia University School of Business.

After her college years, Welty worked at WJDX radio station, wrote society columns for the MemphisCommercial Appeal, and served as a Junior Publicity Agent for the Works Progress Administration. During these years, she took many photographs, and in 1936 and 1937 they were exhibited in New York; but they were not published as she had wished. Her first publication was instead a short story, “Death of a Traveling Salesman.” In 1936, the editor of Manuscript literary magazine called it “one of the best stories we have ever read.”

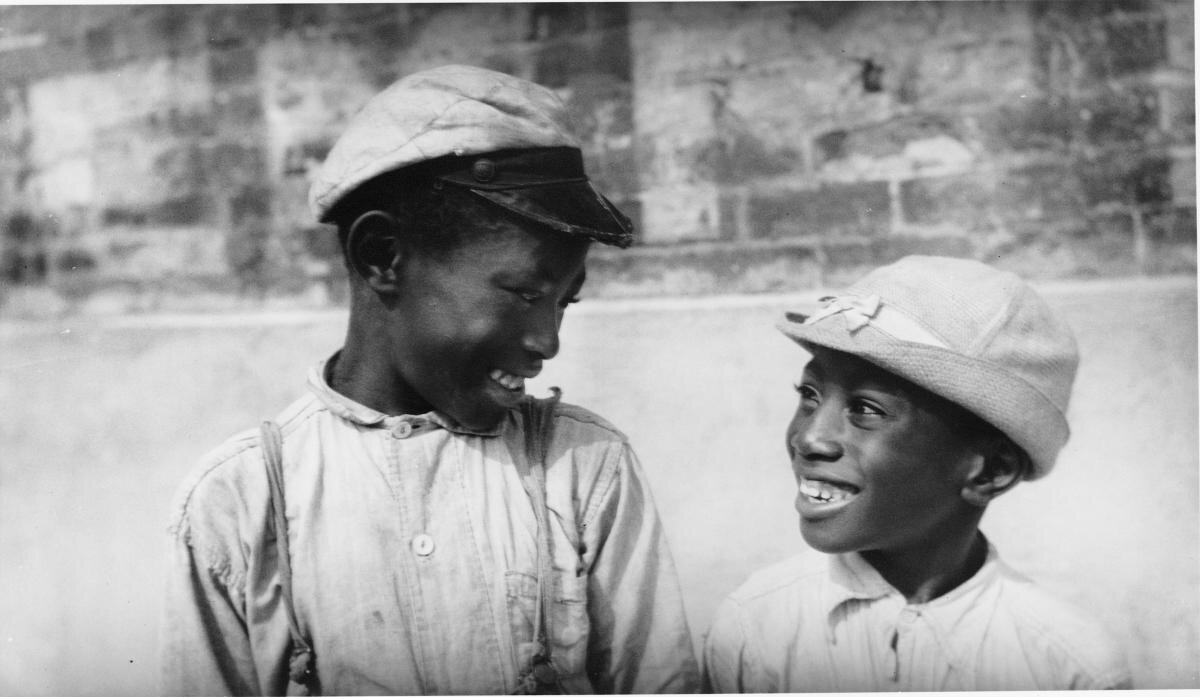

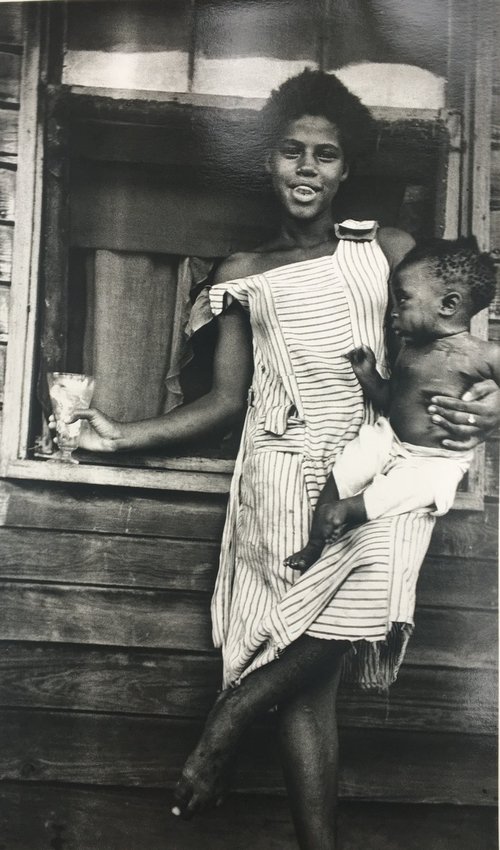

Her first book was published five years later. In A Curtain of Green, Welty included seventeen stories that move from the comic to the tragic, from realistic portraits to surrealistic ones, and that display a wry wit, the keen observation of detail, and a sure rendering of dialect. Here she at times translated into fiction memories of people and places she had earlier photographed, and the volume’s three stories focusing upon African American characters exemplify the empathy that was present in her photos. Toni Morrison has observed that Eudora Welty wrote “about black people in a way that few white men have ever been able to write. It’s not patronizing, not romanticizing — it’s the way they should be written about.”

In 1942, Welty followed with a very different book, a novella partaking of folklore, fairy tale, and Mississippi’s legendary history. A year after this novella appeared, Welty published a third book of fiction, stories that were collected as The Wide Net (1943) and that were fewer in number and more darkly lyrical than those in her first volume. Then came Delta Wedding, her first novel. Set in the Mississippi Delta of 1923, though published in 1946, the book was originally criticized as a nostalgic portrait of the plantation South, but critical opinion has since counteracted such views, seeing in the novel, to use Albert Devlin’s words, the “probing for a humane order.”

In Welty’s next book, the unity of the novel is missing but not wholly. The Golden Apples (1949) includes seven interlocking stories that trace life in the fictional Morgana, Mississippi, from the turn of the century until the late 1940s. When Welty began writing the stories, however, she had no idea that they would be connected. Midway through the composition process, she finally realized that she was writing about a common cast of characters, that the characters of one story seemed to be younger or older versions of the characters in other stories, and she decided to create a book that was neither novel nor story collection. It is perhaps the greatest triumph of her distinguished career, an unmatched example of the story cycle.

After the publication of this book, Welty traveled to Europe and drew upon her European experiences in two stories she would eventually group with “Circe,” a story narrated by the witch-goddess, and with four stories set in the American South. Though the interlocking nature of The Golden Apples is gone, a new theme emerges. Most of these stories investigate the ways individuals can live and create meaning for themselves without being rooted in time and place. Even before she pulled The Bride of the Innisfallen and Other Stories (1955) together, she published The Ponder Heart (1954), an extended dramatic monologue delivered by Edna Earle, a character who truly is a character.

Welty had produced seven distinctive books in fourteen years, but that rate of production came to a startling halt. Personal tragedies forced her to put writing on the back burner for more than a decade. Then in 1970 she graced the publishing world with Losing Battles, a long novel narrated largely through the conversation of the aunts, uncles, and cousins attending a rambunctious 1930s family reunion. Two years later came a taut, spare novel set in the late 1960s and describing the experience of loss and grief which had so recently been her own. Welty would uncharacteristically incorporate a good bit of biographical detail in The Optimist’s Daughter, for which she won the Pulitzer Prize.

Welty’s exploration of such different subjects and techniques involved, of course, more than art for art’s sake. In her essay, “Words into Fiction,” she describes fiction as “a personal act of vision.” She does not suggest that the artist’s vision conveys a truth which we must all accept. Instead, she suggests, the artist, must look squarely at the mysteries of human experiences without trying to resolve them. Eudora Welty’s ability to reveal rather than explain mystery is what first drew Richard Ford to her work. It drew Reynolds Price as well. Price, though, focuses not on the term mystery, but on the complexity of her vision. He writes that Eudora is not “the mild, sonorous, ‘affirmative’ kind of artist whom America loves to clasp to its bosom,” but is instead a writer with “a granite core in every tale: as complete and unassailable an image of human relations as any in our art, tragic of necessity but also comic.”

Welty’s achievements include more than her fiction. Her early photographs eventually appeared in book form: Her photograph book One Time, One Place was published in 1971, and more photographs have subsequently been published in books titled Photographs (1989), Country Churchyards (2000), and Eudora Welty as Photographer (2009). Her essays and book reviews were collected in the 1978 volume titled The Eye of the Story, and her autobiography One Writer’s Beginnings, published in 1984 by Harvard University Press, was a nationwide best seller. For a time during her last three decades, Welty periodically worked on fiction, but completed nothing to her own high standards, standards that made her a literary celebrity. She appeared on televised interviews, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the French Legion of Honor, served as the subject of a BBC documentary, and was chosen as the first living writer to be published in the Library of America series. After a short illness and as the result of cardio-pulmonary failure, Eudora Welty died on 23 July 2001, in Jackson, Mississippi, her lifelong home, where she is buried.

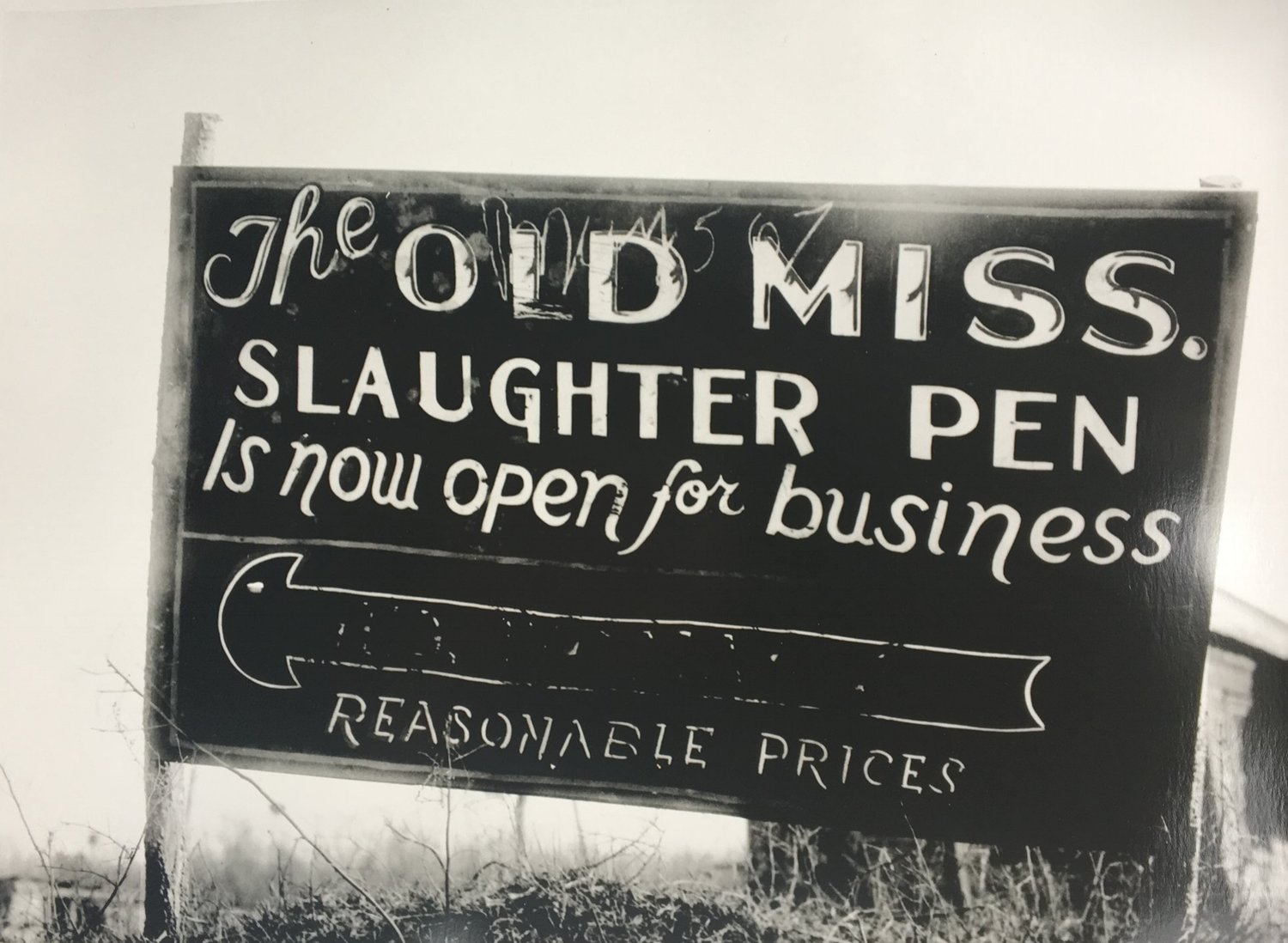

In Photos, Eudora Welty Captured Life in 1930s Mississippi

By Matthew Sedacca for the New York Times

Photographs by Eudora Welty

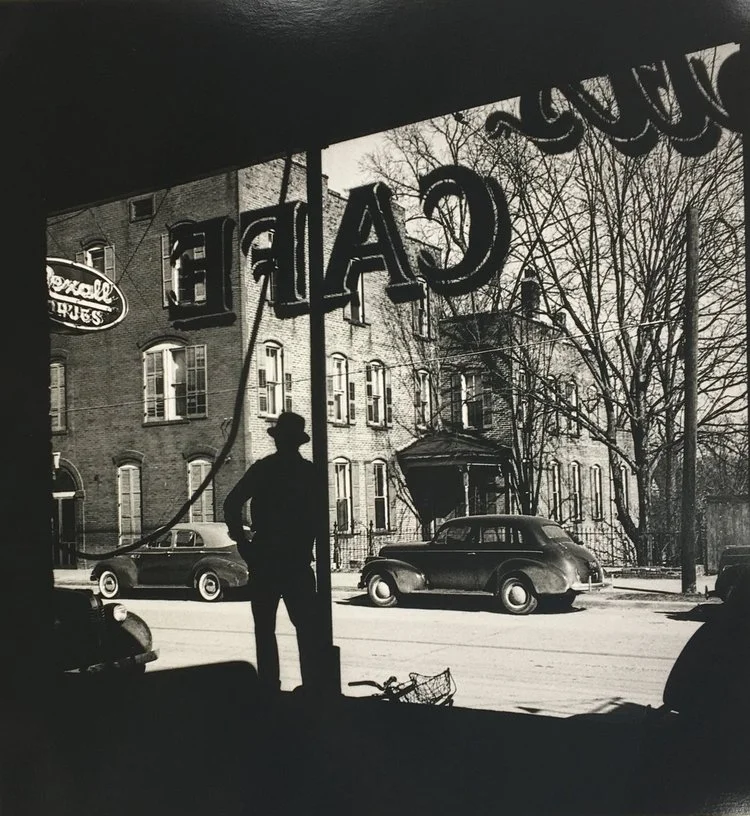

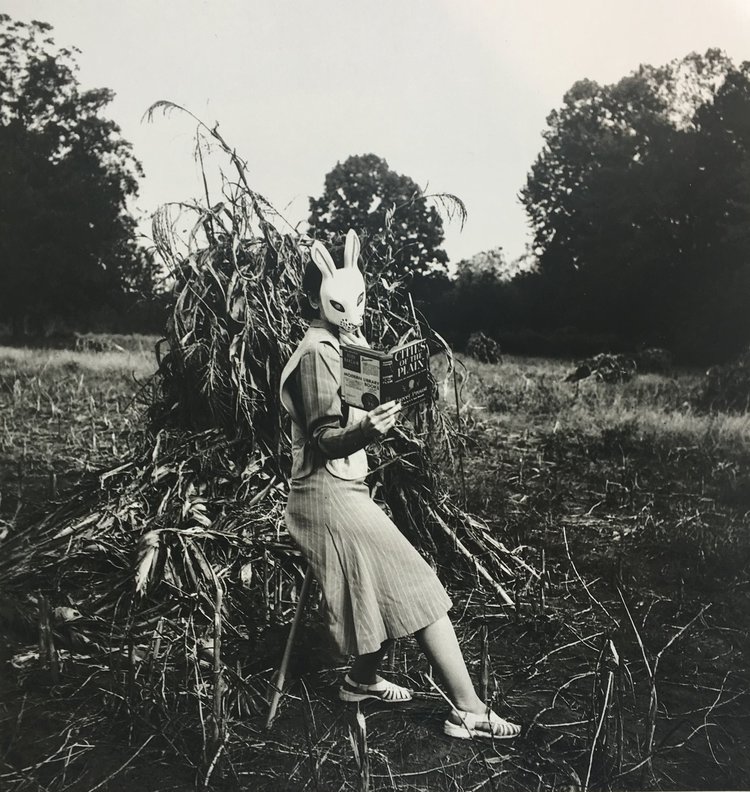

Before her career as a distinguished fiction writer, Eudora Welty applied her short-form prowess to photographing life in Depression-era Mississippi.

Bursting from the fertile ground of Crystal Springs, Miss., an absurdly odd harvest blots out the horizon: a cottage-size tomato, drooping decorative leaf and all, perched atop a wooden shanty. Lured by the irresistible gravitational pull of this shrine to “The Tomatropolis,” a smiling woman poses for a photographer and offers scale, her fingers pointing childlike at the kitsch behind her.

Sure, the folks back home had to see this surreal homage to the city’s economic foundation. But even more unexpected is the photographer: Eudora Welty, the elder stateswoman of American letters.

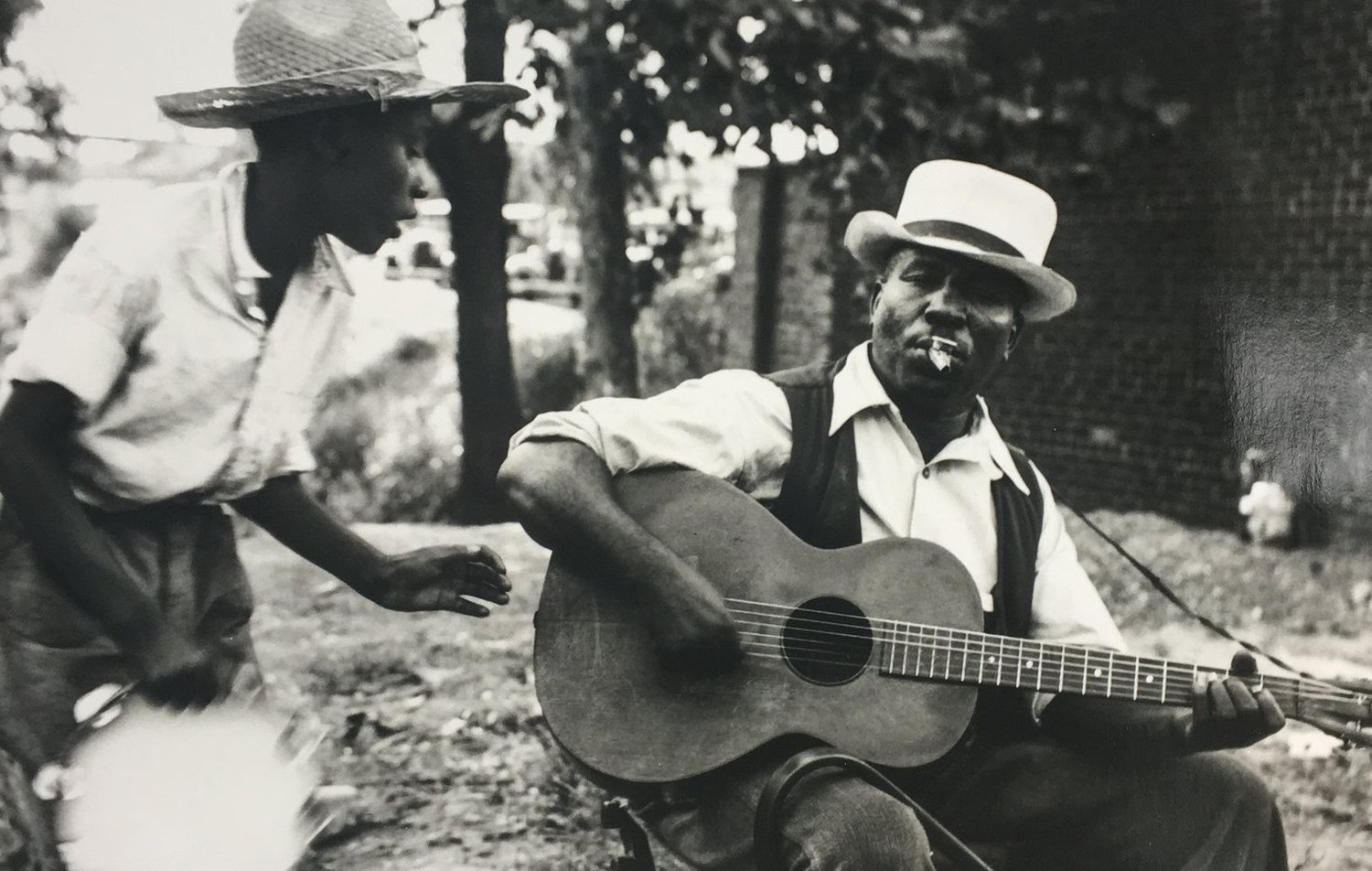

Before becoming famous for her short stories of comedic interfamilial strife and everyday adversities subtly imbued with issues of race and class, Ms. Welty used the camera as her vehicle to preserve life, ever-fleeting with all its joys, complexities and hardships, in the 1930s. Many of these photos were featured in “Photographs,” originally published in 1989, and recently reissued by the University Press of Mississippi.

A native of Jackson, Miss., Ms. Welty briefly left the South to attend the University of Wisconsin at Madison and, later, business school at Columbia University. She returned in 1931 to work at Jackson’s local radio station and contribute society columns to The Commercial Appeal in Memphis.

But it was in her stint as a junior publicity agent for the Works Progress Administration, which itself was famed for dispatching some of the country’s best photographers and writers to chronicle New Deal America, that she flourished as a photographer. Ms. Welty captured her fellow Mississippians in their daily routines, with each frame evoking the complications of everyday life, like children hauling unwieldy blocks of ice to dinner or a fatigued-looking nurse outside a clinic.

“Poverty in Mississippi, white and black, really didn’t have too much to do with the Depression,” Ms. Welty said in an interview with Hunter Cole and Seetha Srinivasan at the beginning of the book. “It was ongoing. Mississippi was long since poor, long devastated. I took the pictures of our poverty because that was reality.”

Prints from this period were featured in her two-week solo show at the photographic galleries of Lugene Opticians in New York in 1936, but the literary world proved more receptive to her work, with Manuscript magazine publishing her first piece of fiction that same year. Her photos were finally published for the first time in her 1971 opus “One Time, One Place: Mississippi in the Depression.”

Given her affiliation with the W.P.A., viewers might be tempted to draw comparisons between her images and those of renowned photographers of the time, like Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, who worked for the Farm Security Administration. The differences between their bodies of work are clear, something she herself confirmed: Instead of the formalism or portrait work of Mr. Evans and Ms. Lange, Ms. Welty’s images show life as it unfolded before her, distilling the solemn quiet of a blind weaver at work or the warm communal embrace of women at a carnival.

“I was taking photographs of human beings because they were real life and they were there in front of me and that was the reality,” Ms. Welty said. “I was the recorder of it. I wasn’t trying to exhort the public.”

Ms. Welty’s photography doesn’t extend past the mid-1950s, a fact she attributed to a combination of losing her camera in Paris and devoting the bulk of her creative energy to writing. Still, the decades spent documenting the world around her played a part in shaping her point of view in writing that people would eventually revere.

“Some perception of the world and some habit of observation shaded into the other,” Ms. Welty said about her dual passions, “just because in both cases, writing and photography, you were trying to portray what you saw, and truthfully. Portray life, living people, as you saw them. And a camera could catch that fleeting moment, which is what a short story, in all its depth, tries to do.”