James Karales | By Rebekah Jacob

he modest Karales only occasionally printed his work and rarely presented it in exhibitions or publications beyond the initial assignment for which it was created. delving into his meticulously preserved archive, I worked to share Karales's voice with a larger audience, focusing on the period 1960-65. Together with Julian Cox, we spent two years editing and sequencing more than 2,000 images to arrive at a final selection of 93 plates. A modest percentage of the images included in this book were published in Look magazine, and some have since been reproduced in books and magazines, but the majority have never been exhibited or published. Our extensive research also included the study of vintage prints in museum collections, the Karales Archive in the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library at Duke University, and a thorough review of the Look archives at the Library of Congress. Photographs consigned from the Howard Greenberg Gallery and the Rebekah Jacob Gallery in Charleston, South Carolina, were also vital resources. Recollections shared by Karales's contemporaries Tony Vaccaro, Bob Adelman, Steve Shapiro, Matt Herron, and Paul Fusco added an invaluable human dimension to the project.

The modest Karales only occasionally printed his work and rarely presented it in exhibitions or publications beyond the initial assignment for which it was created. delving into his meticulously preserved archive, I worked to share Karales's voice with a larger audience, focusing on the period 1960-65. Together with Julian Cox, we spent two years editing and sequencing more than 2,000 images to arrive at a final selection of 93 plates. A modest percentage of the images included in this book were published in Look magazine, and some have since been reproduced in books and magazines, but the majority have never been exhibited or published. Our extensive research also included the study of vintage prints in museum collections, the Karales Archive in the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library at Duke University, and a thorough review of the Look archives at the Library of Congress. Photographs consigned from the Howard Greenberg Gallery and the Rebekah Jacob Gallery in Charleston, South Carolina, were also vital resources. Recollections shared by Karales's contemporaries Tony Vaccaro, Bob Adelman, Steve Shapiro, Matt Herron, and Paul Fusco added an invaluable human dimension to the project.

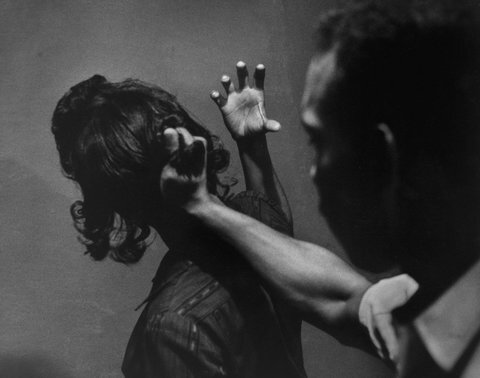

The 190s were the heyday of the great photography magazines, providing working photographers with the opportunity to capture the spirt of the time in elaborate, multipage spreads with large images. Civil rights leaders embraced the medium as a vehicle to inform and educate the general public and as a means to document their momentous journey. Magazines were hungry to print images from the front lines. Despite the dangers for journalists, photographers were drawn to the drama of the civil rights story and provided valuable witness to the demonstrations, arrests, riots, and burnings.

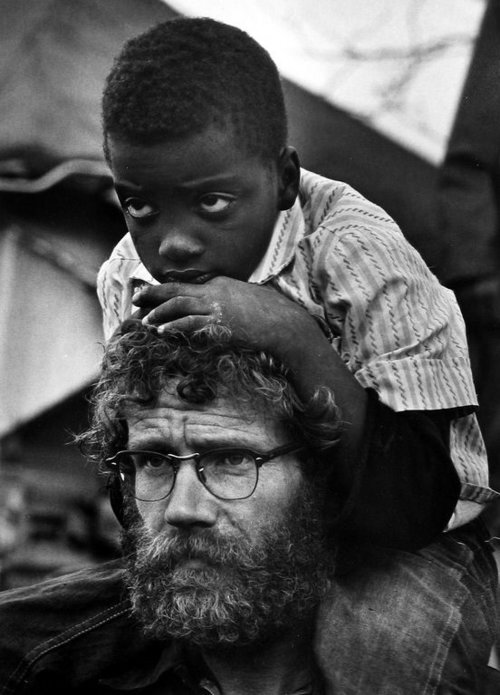

With several camera slung around his neck and a cigarette in one hand, Karales focused his intense glaze on one of the most challenging issued in our nation's history. He balanced the job's requirements with is own aesthetic to find a different story, one of tenderness and triumph. Within the crowds his discerning eye discovered heroic portraits of individuals, such as a teenage boy enveloped by a massive, hand-stitched flag, or a youth with "vote" emblazoned across his forehead.

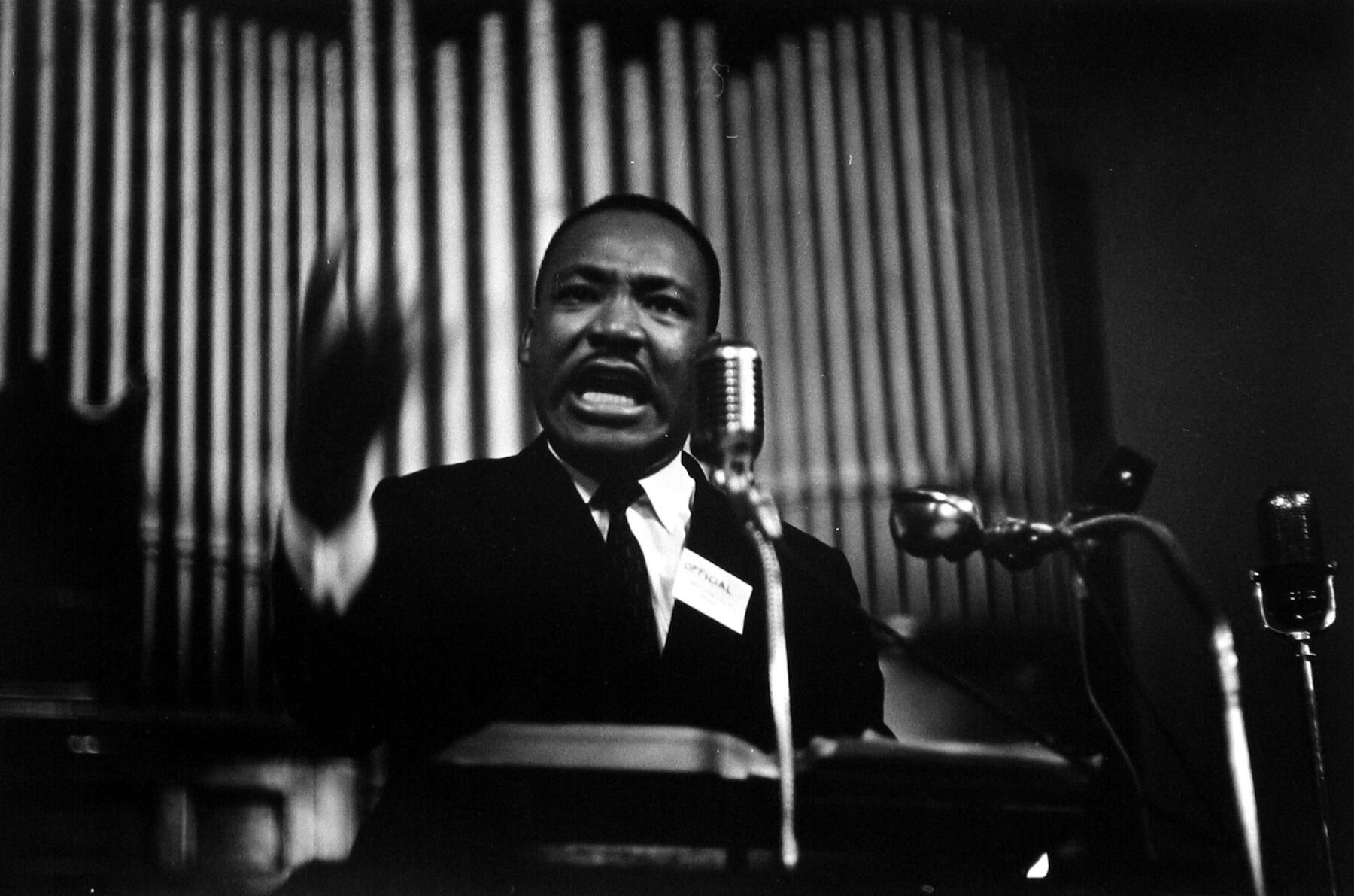

Arguably the most signifiant work at this time comes from Karales's close access to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and other key civil rights leaders. One of only a few photographers to enter King's home, Karales crated images of Dr. King that go beyond the expected to portray quiet, telling moments. One photograph reveals Dr. King's fatherly angst as he painfully broke the news to his young daughter that she was forbidden to visit an amusement park because of her race. The caption in the February 12, 1963, issue of Look reads: "I told my child about the color bar."

The photographs in this book, Controversy and Hope: The Civil Rights Images of James Karales, present the range of civil rights assignments that Karales undertook in teh years 1960-1965: nonviolent passive resistance training in Atlanta in 1960; the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) convention in Birmingham in 1962; an intimate series of the King family at home in Atlanta in 1962; Dr. King and Rev. Ralph Abernathy's campaign in Birmingham in 1962, which includes pictures made in the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, with Rev. C.T. Vivian, Rosa Parks, and other leaders in attendance. The story concludes with a selection of images documenting the Selma to Montgomery March for Voting Rights in 1965, which provided the culminating and iconic images of a movement that had become so personal Karales.

Despite the passage of time, or perhaps heightened by it, we are able to see the integrity and clarity of Karales's vision against the backdrop of a crucial juncture in our shared history. His work continues to compel us to remember both what divides us and what unites us. It is my hope that this publication reveals previously untold moments in this pivotal era of American history.

Preface by Rebekah Jacob, published in Controversy and Hope: The Civil Rights Photographs of James Karales, published by the University of South Carolina Press, 2013.